International Municipal Lawyers Association - Local Government Blog

RLUIPA Ripeness Rule Reinforced

1 Comment

The concept of ripeness in several realms is elusive. I have never figured out how to properly thump a melon at a grocery store, although I have made a thorough study of it. You might want to click here, or here, or here for some guidance, none of which seems to work when it’s just me in a stare down with a cold, stone faced and silent honeydew.

Just yesterday one of my younger children from what we call the “second litter” asked me at dinner how I could tell if a coconut was ripe. I paused, realized that I had no answer, and did what every good parent should do and asked instead why they weren’t eating their salad. Yes, attack and divert.

You think melons and coconuts are tough — try ripeness in land use litigation. It has been a battleground in regulatory takings. No one seems to like the current rules. Here’s an article which you might find useful for background. Even Professor Daniel R. Mandelker of Washington University in St. Louis, who is a self-styled “police power hawk” (meaning he is almost always on the side of planning, regulation and government), doesn’t like the current ripeness rules and testified in the U. S. Congress about what it should do to fix the situation. Professor Mandelker co-hosts IMLA’s teleconference series “Mondays with Mandelker and Merriam.” Click here for information.

Ripeness is a good defense for government lawyers and ripeness rules do make sense where they prevent a case from being tried prematurely, because it is almost always better for all concerned if property owners and government have an opportunity to resolve their differences. Ripeness, at least as it applies to inverse condemnation, has two prongs. First, the government must reach a final position so that everyone knows what can be approved and what won’t be. The second prong is that a property owner must seek compensation in the state courts before proceeding to the federal courts for relief.

That first finality prong of ripeness made its way into litigation under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) in the case of Murphy v. New Milford in the Second Circuit.

On Wednesday, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit handed down a decision in Congregation Anshei Roosevelt v. Planning and Zoning Board of the Borough of Roosevelt in which it adopted the ripeness rule applied in the Murphy case. The lawyer for the Borough of Roosevelt was Professor Marci Hamilton, who will be the guest of Professor Mandelker and me on our IMLA teleconference next Monday, August 3rd. She also represented New Milford in the Second Circuit in the Murphy case.

In Murphy, the complainants were conducting prayer meetings at their home. Those meetings became more frequent and attracted larger numbers of people. The zoning enforcement officer issued a cease and desist order on the ground that the use of the property for a religious institution was not permitted. The Murphys went to federal court and won on their RLUIPA claim. However, the Second Circuit said that the case was not ripe for adjudication because the Murphys had not appealed the cease and desist order or applied for any local zoning relief such as a variance.

In Roosevelt, the Congregation Anshei Roosevelt brought an action in federal district court in New Jersey against the Borough of Roosevelt, its mayor and council, and its planning and zoning board under RLUIPA and state law. The defendants moved to dismiss claiming that the matter was not ripe for judicial review. The federal district court granted the motion to dismiss and on appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, that court affirmed the district court’s dismissal.

The Congregation established a small New Deal resettlement in the Borough long before zoning was enacted. Under current zoning regulations, the pre-existing, non-conforming synagogue has been allowed to continue.

In 2005, the Congregation entered into an agreement with the Yeshiva under which the Yeshiva would provide the Congregation with rabbinical services and the Congregation in turn would allow the Yeshiva to conduct study and worship activities at the synagogue. The Yeshiva began its operations, a neighbor complained, the zoning officer consulted with the Borough attorney, and it was ultimately decided that the activity could continue as part of the non-conforming use.

Enter the concerned citizens group, the Roosevelt Preservation Association. The Association appealed the zoning officer’s decision to the Planning and Zoning Board. Hearings were held. A rabbi testified as to why a Yeshiva is necessarily is part of a synagogue, the neighbors testified that there were 34 students enrolled and that those students congregated on the property and the street and that there many cars coming to and from the Yeshiva.

The Board ultimately overturned the decision of the zoning officer and said that the Yeshiva would need a variance to operate there. In the Board’s view requiring an application for a variance would not be a substantial burden on the congregation and the Yeshiva.

In the Court of Appeals, the Congregation and the Yeshiva argued that the case was ripe because the Board had reached a final determination on whether the Yeshiva was a house of worship use and therefore permitted as a pre-existing, non-conforming use and that the Board had also decided that the current zoning regulations were applicable to the property.

In handing down its decision, the Court of Appeals noted that ripeness is a jurisdictional inquiry under Article III of the U. S. Constitution. The Court went on to cite the leading inverse condemnation case in this area, Williamson County Regional County Planning Commission v. Hamilton Bank of Johnson, U. S. Supreme Court (1985) and quoted from it noting that the takings claim as decided in that case was “not ripe until the government entity charged with implementing the regulations has reached a final decision regarding the application of the regulations to the property at issue.”

The Court of Appeals also cited Murphy and the four reasons for requiring ripeness: it helps develop the full record, it provides the Court with knowledge as to how the regulation will be applied to a particular property, it may avoid litigation all together if the local government gives the relief sought, and it shows “the judiciary’s appreciation that land use disputes are uniquely matters of local concern more aptly suited for local resolution.”

The Court of Appeals said that the Board had not determined that the Yeshiva was not a permitted use, but had only found that there was a “significant increase in the intensity of that use” and that the variance was necessary to “consider the effect on the neighborhood.”

As so the claim that the Board had made a final determination with regard to the application of the zoning rules at this property, the Court discussed the land use aspects of RLUIPA and ultimately determined that “[t]he factual record is not sufficiently developed to decide fully the RLUIPA claim here, and the Board has not issued a definitive position as to the extent the Yeshiva can operate on the synagogue property.”

The pièce de résistance is what every local government lawyer and planner likes to hear from a federal court: “Finally, we have stressed ‘the importance of the finality requirement and our reluctance to allow the courts to become super land-use boards of appeals. Land-use decisions concern a variety of interests and persons, and local authorities are in a better position than the courts to assess the burdens and benefits of those varying interests.’”

Time and time again federal courts have stated emphatically that they do not want to be “super land-use boards of appeals,” and consequently they have, in most cases, supported ripeness rules that require finality in the decision making process at the local level.

The Third Circuit has marked the decision as “not precedential.” However, the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure were recently amended to allow the decision to be cited.

Rule 32.1 Citing Judicial Dispositions

(a) Citation Permitted. A court may not prohibit or restrict the citation of federal judicial opinions, orders, judgments, or other written dispositions that have been: (i) designated as unpublished, not for publication, nonprecedential, not precedent, or the like; and (ii) issued on or after January 1, 2007. (b) Copies Required. If a party cites a federal judicial opinion, order, judgment, or other written disposition that is not available in a publicly accessible electronic database, the party must file and serve a copy of that opinion, order, judgment, or disposition with the brief or other paper in which it is cited.

The debate continues on how these nonprecedential decisions can be used. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1280962.

Meanwhile, I will go on mindlessly thumping the honeydews…

What Happens When an Irresistible Force Meets an Immovable Object – A Moratorium to Promote Sustainable Development Runs into the Constitutional Right to the Exercise of Religion

Leave a Comment

Posted By: Dwight Merriam, Partner, Robinson & Cole, LLP

The unstoppable force paradox is an exercise in logic that seems to come up in the law all too often. There is a Chinese variant. The Chinese word for “paradox” is literally translated as “spear-shield” coming from a story in a Third Century B.C. philosophy book, Han Fiez, about a man selling a sword he claimed could pierce any shield. He also was trying to sell a shield, which he said could resist any sword. He was asked the obvious question and could give no answer.

The Washington Supreme Court broke the paradox between a 12-month moratorium during which the City of Woodinville considered sustainable development regulations for its R-1 residential area, and the efforts by the Northshore United Church of Christ (Northshore Church) to host a movable encampment for homeless people on its R-1 property. City of Woodinville v. Northshore United Church of Christ (July 16, 2009).

Throw into the mix the Washington State Constitution and the federal Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) and you have enough irresistible forces and immovable objects to fill any Chinese philosopher’s book.

The encampment of 60-100 people in the Puget Sound area moves from place to place every 90 days. When it came time for it to move, and Northshore Church applied for a temporary use permit, the city refused to act on it based on the moratorium put in place just a few months before.

Here is the encampment from the city’s website:

Here’s another photograph, courtesy of MyNorthwest.com which also has a story on the case and a KIRO radio report.

Northshore Church sued. The city won at trial and got an injunction against the encampment. The trial court held that the city met its obligation to have a narrowly tailored moratorium that achieved a compelling governmental purpose – thus, there were no constitutional or RLUIPA violations. The appellate court upheld the trial court, even though it found that the trial court should not have applied strict scrutiny.

The Washington Supreme Court reversed, holding that the city could not refuse to process the application because the Washington Constitution guarantees “[a]bsolute freedom of conscience in all matters of religious sentiment, belief and worship…[and] shall not be so construed as to … justify practices inconsistent with the peace and safety of the state.” The refusal to process the application was a substantial burden, said the court, because “[i]t gave the Church no alternatives.”

The Court did not reach the RLUIPA claim as it held the constitutional violation was dispositive.

The city’s website describes the appellate court decision, but does not report the Supreme Court’s reversal. Northshore Church’s website, however, celebrates the decision.

The key point is the utter lack of any alternatives. The city simply refused to process the application. Northshore Church said at oral argument that it could have hosted the encampment inside the church (sounds like new evidence to me – surprising how often this kind of thing sneaks in during appellate argument) and the Washington Supreme Court noted this as illustrative of how refusing to process the application precludes considering any alternatives. Almost as important was the moratorium of 12 months and the Washington Supreme Court’s precedential decision that a 14-month delay created an unconstitutional burden. The city had not shown the moratorium to be a narrow means of achieving a compelling goal. “Planning pause” moratoria, as we call them, are hard to justify beyond six months and most moratoria should allow some administrative relief for exceptional cases. This is one of those exceptional cases, where the permit was for a temporary use, a use not likely to defeat the purpose of this moratorium to study how to have more sustainable development in a residential zone.

Tags: church, development, Dwight, encampments, homeless, Land, Merriam, permit, RLUIPA, sustainable, temporary use, use moratorium

Town Attorney Not Disqualified from Representing Town in Litigation on the Same Matter Where He Provided Advice to the Zoning Board

Leave a Comment

Posted By: Professor Patricia E. Salkin

Most municipalities across the country are small and cannot afford separately retained legal counsel for its legislative body and all of its various boards, commissions and departments. While best practices might dictate separate and specialized legal counsel for the executive and legislative branches of municipal governments, as well as for the planning and zoning boards (where a disproportionate amount of municipal litigation occurs), the reality is that only the larger city and suburban towns routinely operate this way. There are no doubt, however, instances where the interests of two or more entities within the same municipality are in conflict, and in these cases, it is clear that each entity is entitled to its own independent legal counsel. Numerous state bar association opinions speak to this issue (e.g., when the zoning board is being sued by the legislative body). Recently, the Maine Supreme Court had occasion to address the issue of whether it is a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct for a town attorney to represent the town in litigation stemming from advice the attorney gave to the zoning board of appeals. The facts are as follows:

On the advice of legal counsel, the Zoning Board of Appeals of the Town of Westport Island refused to grant standing to residents wishing to challenge the planning board’s approval a permit requested by the Town Board to make improvements to the public boat-launching site. Residents opposed to the issued permit argued, among other things, that the Town Attorney should be barred from representing the Town in litigation over the standing issue since he served as an advocate and legal advisor to the zoning board on the same matter.

The Court concluded that while the Maine Bar Rules do prohibit attorneys from serving certain dual roles, in this case the representation was not in conflict. Specifically, Rule 3.4(g)(2)(i) states:

A lawyer shall not commence representation is a matter in which the lawyer participated personally and substantially as a judge or judicial law clerk. A lawyer shall not commence representation in a matter in which the lawyer participated personally and substantially as a nonjudicial adjudicative officer, arbitrator…or law clerk to such a person, unless all parties to the proceeding give informed consent.

The Court explained that since the zoning board is a branch of the Town, the attorney was simply doing his job as the Town’s legal representative when he advised the zoning board on the standing issue. The Court said that the attorney did not act in a judicial or quasi-judicial capacity and hence the Bar Rule was not implicated here and the motion to disqualify was properly denied.

Nergaard v. Town of Wesport Island, 2009 WL 1522707 (Me. 6/2/2009).

Development Opposition Results in Civil Stalking Protection Order

Leave a Comment

Posted By: Dwight Merriam, Partner, Robinson & Cole, LLP

I get back from a nice nine days cruising in my sailboat to face over 1,000 emails and there in the midst of them is a slip opinion in a land-use civil stalking complaint. It kind of makes me want get back onboard with Captain Morgan and sail away…

Thanks (I guess) to my friend, Stuart Meck, FAICP/PP, Associate Research Professor and Director, Planning Practice Program at the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, for this little gem. (Stuart — your title is longer than my resume, for heaven’s sake). Stuart was from Ohio in another life and with Kenneth J. Pearlman publishes the annual treatise, Ohio Planning and Zoning Law (Thomson West). Stuart’s a planner, not a lawyer, but he knows land use law.

The back story is this. Three 20-something idealists decide to do an ambitious mixed use project in Oberlin, Ohio. It even gets the attention of The New York Times in 2006. Here are the young entrepreneurs courtesy of The New York Times.

Ben Ezinga, left, Naomi Sabel and Joshua Rosen, collectively known in Oberlin, Ohio, as “the kids,” put together the financial backing and city support for a $15 million development on a site vacant for years. David Maxwell for The New York Times

Their project was budgeted at $15 but became $17 million and includes 28,000 square feet of retail space, 52,000 square feet of residential space and about 15,000 square feet of parking. They closed on the financing and have the project under construction.

The string of messages spanning almost three years on this blog is a good read. The threesome calls themselves Sustainable Community Associates and their website has detailed information on the project. You can see the construction underway on videos they have posted at the website. Many recent photographs (July 8, 2009) are available on flickr.

Nice story; happy ending forthcoming, I assume, if the rotten real estate economy doesn’t take them down.

However, early on, one Mark Chesler became a vitriolic opponent. Click on this and read some of his testimony and think back to those hearings when you sat through similar diatribes. And if you want more, click here.

It got so bad that Rosen sought and was granted a civil stalking protection order against Chesler, who allegedly yelled things at Rosen on the street 7-10 times in two months before the order was issued. The court issuing the order (actually adopting a magistrate’s decision) and the court on appeal found a “pattern of conduct” which is two or more actions or incidents closely related in time. One of them was in a restaurant where Chesler yelled at Rosen: “I got you now.”

A few days later Chesler confronted Rosen downtown. There were other encounters reported in the decision by the Court of Appeals Ninth Judicial District on June 30, 2009, upholding the order. Rosen feared bodily harm.

This land-use business can be tough.

Tags: apartments, Dwight, Land, Merriam, mixed-use, oberlin, order, restraining, Use

And the Rockets’ Red Glare, the Bombs bursting in air,… – Francis Scott Key (1814)

Leave a Comment

Special July 4, 2009 Edition

Posted By: Dwight Merriam, Partner, Robinson & Cole, LLP

Happy Independence Day. By the time this is posted, I hope to be celebrating our country’s birthday at Block Island aboard our J/105 sailboat, ORIANA.

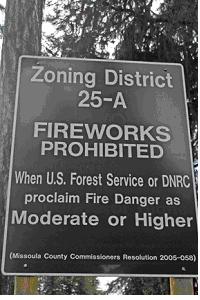

Fireworks are a serious business. Look at this sign, for example:

Courtesy Missoula County

Sweetwater County, Wyoming has a useful form for the seasonal sale of fireworks.

York County, South Carolina has a list of requirements for temporary fireworks stands.

Irwindale, California has some detailed regulations. The provision I like the best is this one at Section 8.16.090: “…nor shall any person smoke within such stand or other places of sale or within twenty-five feet thereof.” You would think this kind of thing doesn’t need to be said.

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma charges a fee based on the length of the fireworks stands.

Litigation over fireworks usually seems to start with a fire and an explosion, as in the nonconforming use case of Midwest Fireworks v. Deerfield where the fireworks company proposed to rebuild at four times the size of the buildings destroyed. What happens when the fireworks stand is closed down most of the year and wants to reopen after a new, restrictive law goes into effect? The Municipal Technical Advisory Service has an 11-page, single-spaced opinion letter on the subject, at least as to Tennessee, though much of the discussion cites cases across the country and is useful elsewhere.

Happy Fourth of July!